To read this newsletter in an easy pdf format, click here to download Constructing Complete Proteins from Plant Foods

The livestock sector emerges as one of the top two or three most significant contributors to the most serious environmental problems, at every scale from local to globaland should be a major policy focus when dealing with problems of land degradation, climate change and air pollution, water shortage and water pollution, and loss of biodiversity

Livestocks contribution to environmental problems is on a massive scale and [yet] its potential contribution to their solution is equally large.

Livestocks Long Shadow, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), United Nations

This newsletter was inspired by the current pressure on family food budgets brought about by the recent cutbacks in food assistance programs and by the severe 2013-14 drought that has caused cattle farmers to trim herds to a 21-year low. It is also inspired by todays serious environmental concerns and the threat of global warming. But, while the confluence of cutbacks in food assistance, rising meat prices, and global warming challenge us, they also offer the opportunity to return to the basic nutritional wisdom of prior generations. Traditional cultures instinctively knew how to combine plant foods for good nutrition. By understanding how to construct complete proteins from plant foods and exploring American and ethnic recipes, plant-based complete-protein meals can become economical favorites that enable us to play a role in preserving the environment, right in our own homes.

On November 1, 2013, the 2009 Recovery Acts temporary boost to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) ended. As a result, benefits for SNAP households were cut significantlyby $36 a month for a family of four, to a level where SNAP now provides an average of just $1.40 per person per meal. Meanwhile, an eight-year drought and higher grain prices have forced farmers to trim herds, putting another pressure on food budgets. According to the USDA, in January 2014, retail beef prices were at or near record high inflation-adjusted levels. And, as farmers now hold back cattle to rebuild herds, beef prices are expected to increase again, by 10%-15% this year, as well as throughout 2015.

The Environment. At the same time that trimming herds squeezes pocket books, it also brings with it a clear short-term plus by slowing climate change. This potential is easy to see given livestock productions large footprint on our global ecosystem, as well as its huge contribution to our greenhouse gas problem: Through grazing and the raising of feed crops, livestock production worldwide accounts for 70 percent of all agricultural land and 30 percent of the earths surface. And, with respect to global warming, the FAO conservatively estimates that livestock production explains for 18 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions, measured in CO2 equivalenta share greater than the entire worldwide transportation sector. [Jess McNally of Stanford points out that, depending on how the figure is calculated, instead of 18 percent, livestock may explain as much as 51 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions measured in CO 2 equivalent.] According to the FAO, livestock production also accounts for 37 percent of anthropogenic methane, which has 23 times the global warming effect of CO2, as well as (largely through manure) 65 percent of anthropogenic nitrous oxide, which carries 296 times the global warming impact of CO2.

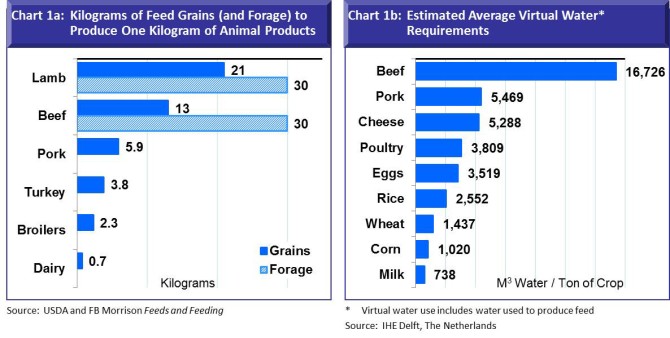

Apart from greenhouse gasses and global warming, other major long-term environmental impacts of the growth of livestock production include deforestation, especially in Latin America, as forests are cleared to create pasture and to raise feed crops; depletion of the water supply (two-thirds of the world population are expected to live in water-stressed basins by 2025); and accelerated threats to biodiversity. Clearly, these problems will not be resolved by short-term, drought-related cuts in livestock production.

Nor can we count on the worldwide livestock production/environmental picture to brighten in the future: With expanding populations and incomes, global demand for meat is projected to double in the 50 years 2000-2050. This makes it all the more important that we find greater environmental efficiencies in livestock production; rely more on animal proteins like poultry and fish that have less of an environmental impact; and shift to more plant-based proteins in countries that overly rely upon meat and have a protein-margin to do so.

Omnivores Dilemma?

With the current pressure on household food budgets and environmental issues, Michael Pollans Omnivores Dilemma of 2006 seems all the more fitting today. Meat devotees and vegans face off using some of the following arguments

Meat lovers point to the fact that only animal-based foods supply complete proteinsproteins that include not only the broad array of all 22 amino acids, but also an abundant supply of the 9 essential/indispensable amino acids, those that the body cannot synthesize on its own. In addition, meat is the only viable dietary source of both vitamin B12 and easily absorbable (heme) iron. Animal proteins are also easier than plant proteins to assimilate, a factor especially important as people age: Ruminants act as a kind of walking processing plant doing all the grass/grain-to-protein conversion work for ussomething our mono-gastric systems cannot easily do. In favor of eating animals, some advocates of meat may also point to the jaw structure of humans to validate their claim that we are naturally designed to consume animal flesh.

Meanwhile, vegan/vegetarians will argue for a plant-based diet, believing it is more humane, easier on the pocketbook, and less costly to the environment. In addition, a plant-based diet is associated with a lower risk of chronic health issues, particularly obesity, diabetes, cancer, and cardio-vascular disease. Plant foods also provide fiber and a host of micronutrients and antioxidants that work synergistically to support health in a variety of ways, many of which are not yet understood by science. Another important consideration is that avoiding commercially-raised animal products is one of the best ways to prevent the unintentional, indirect consumption of hormones, antibiotics, food additives, and GMOs (through GMO feed crops such as soy and corn)all silent elements that are ingested with commercially-raised animal products.

If we look at the animal/plant protein question simply from a health standpoint, it is certainly true that most people feel best consuming a diet that includes some animal proteins, particularly during the growth years and in the later decades of life. The goal of this piece is not to advocate for a strict vegan diet. A vegan diet can work well for many young adults who are able for a time to run on what Traditional Chinese Medicine terms kidney essence energy (the finite dry-cell battery pack gifted at birth). But as people age, digestive systems tend to weaken, as does the ability to extract vitamin B12 from dietary proteins, so with advancing years, protein requirements can, in fact, increase. So, for the vast majority of people associated with the aging postwar baby boom, easy-to-assimilate animal proteins (for example, economical foods using bone stocks) may become increasingly important.

Beyond our own health considerations, of course, is the overriding concern posed by the environment, to which our own health is inextricably tied. Within this context, it seems urgent that people in countries with a comfortable animal-protein margin understand how and be willing to trade some animal proteins for plant-based foods.

Protein and Protein Requirements

The word protein, from the Greek proteos, means taking first place, something that points to the long-standing recognition of the key role that protein plays alongside its macronutrient partners, carbohydrates and fats, in supporting good health. Consuming adequate dietary protein is essential to supply the body with both indispensable amino acids (those it cannot make on its own) as well as nitrogen. With these as raw materials, the body can then synthesize the many proteins and nitrogen-based molecules it needs for its many vital functions: Proteins, which are the major component of cells, are used not only in routine cell maintenance and replacement, but also for building enzymes; hormones; tissue and bone; immunity/ antibodies; transport carriers to and from cells; and as buffers to regulate pH.

How much protein do we need? According to Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine, the recommended protein daily allowance (RDA) for adults is 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, which translates to 0.36 grams of protein for every pound a person weighs. This means that someone weighing 140 pounds might require about 50 grams of protein/day; while the RDA for a 180-pound adult would be ~65 grams of protein (package labels on foods can help you with this). There are no hard and fast rules, however, because protein and amino acid requirements vary from individual to individual depending on age, body type and size, general health, activity and lifestyle. Also, as a general guideline, at similar weights, protein requirements are about 20 percent higher for males; they are also about 50 percent greater for pregnant and nursing women. Stress requires greater protein intake, as well, because stress hormones accelerate protein metabolism.

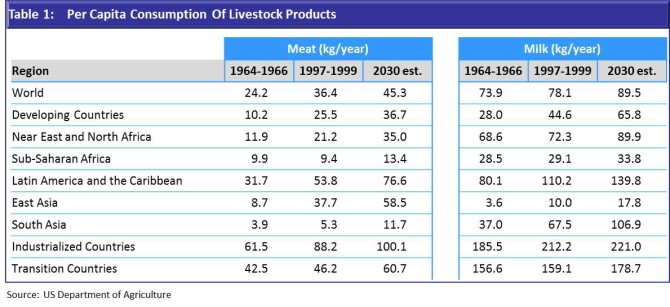

The Standard American Diet (SAD) presents little risk of protein deficiency. For industrialized nations like the United States, per capita consumption of both meat and dairy is more than twice the global average, a multiple that is expected to remain the same through 2030 (Table 1). On a per capita basis, the industrialized world consumes almost 10 times the meat and dairy of protein-deficient South East Asia, for example. South East Asians are typically people of short stature, a trait that is partly linked to their heavy reliance on grains, which lack lysine (lysine is important for growth). The tall stature of most Americans is one measure of our protein affluence. A simple test of protein status, no matter your height or build, is to assess the condition of hair, nails, and ease of wound healing.

While not enough protein can undermine health, so, too can too much since excessive protein can lead to an overly-acid condition of the blood. Large amounts of high-protein, acid-forming (low pH) foods such as meat, poultry, fish, eggs, cheese (and soft drinks) without adequate intake of alkalizing (high pH) vegetables and fruits to buffer the acids from high-protein foods force the body to find its own alkalizing buffers. As a last resort to deal with acidic conditions, the body will tap into its precious stores of calcium and magnesium, minerals housed largely in the bones (think osteoporosis). [Excess acids are normally excreted through the kidneys via urine, but the system set up long ago by Nature whereby the pH of urine is unable to dip far into the acid range means the body has a hard time dealing with the Standard American Diet of today. Urine can only do so much to correct for the excessive acid-forming foods that characterize the Standard American Dietleaving the body to top into its mineral stores to deal with the rest.]

Comparing Animal Proteins and Proteins Created by Combining Plant Foods

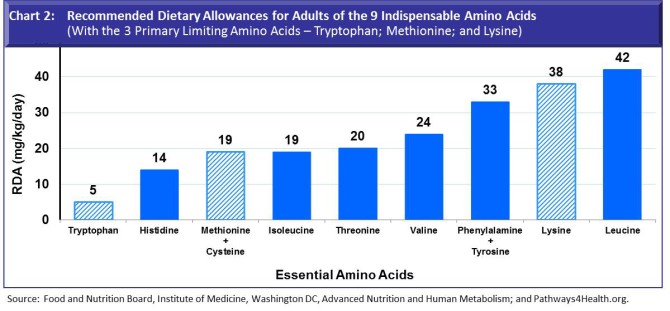

As mentioned above, consuming adequate dietary protein helps supply the body with the 9 indispensable amino acids that it cannot make on its own, as well as with nitrogen, the building block that allows the body to synthesize the remaining complement of 13 amino acids. The quality of protein provided by a food is most importantly set by its profile indispensable amino acids (IAAs), both in terms of the overall quantity of IAAs that the body requires, as well as the proportions of IAAs needed in relation to each other (see Chart 2). Protein quality is also affected to a lesser extent by its digestibility, a quality that is somewhat controversial, because it can be measured in a variety of ways. Regarding the digestibility of proteins in foods, it is best to use large ranges and think of figures as rough estimates. Also as a side note, the assimilation and digestibility of plant-based amino acids as found in grains, legumes, nuts and seeds is hampered by phytates, a defense inherent in seeds to protect their vital essence. Grains and legumes need to be soaked to diffuse phytates, which would otherwise block the bodys ability to utilize selected enzymes and their vital minerals.

Animal proteins (except gelatin, which lacks tryptophan) are complete proteins because they include all the indispensable amino acids in sufficient amounts to meet the bodys requirements. In contrast, proteins found in plant foods are incomplete, with the exception of soy and the grains amaranth and quinoa.

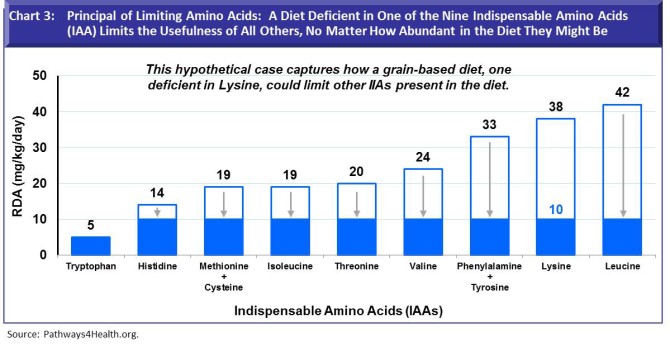

Plant foods are incomplete because they have too little of one or more of the indispensable amino acids. Protein synthesis requires a perfectly-matched, complete set of indispensable amino acids. The least of any indispensable amino acidtermed the limiting amino acidlimits the role of all the rest, no matter how abundant (see Chart 3). The three primary limiting amino acids in plants foods are lysine (deficient in grains); methionine (lacking in legumes); and tryptophan (shy in corn). In this example, a deficiency of lysine (10 rather than 38 in the example below), something that characterizes a grain-based diet, limits the effectiveness of all other essential amino acids that are present.

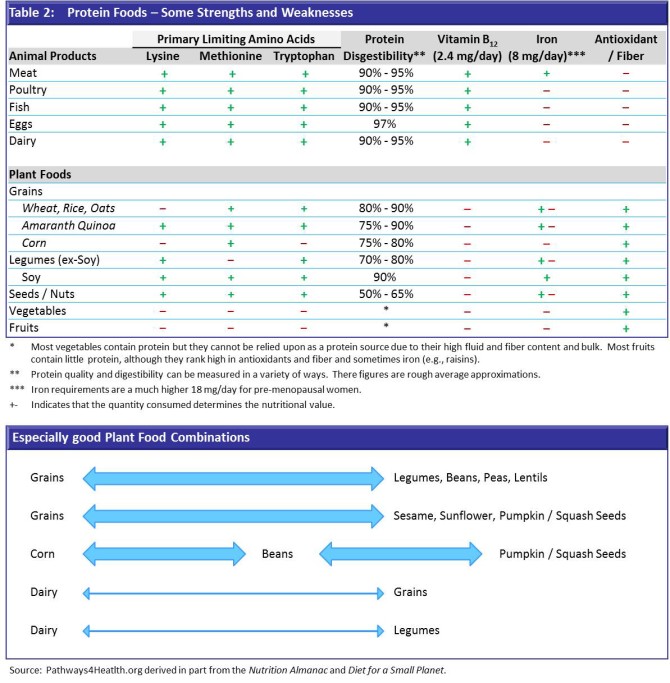

The principle of limiting amino acids makes it all the more important to understand some of the simple principles for constructing complete proteins from plant foods (see Table 2 constructed below, as a guide). Successful plant food combinations can be constructed using Table 2 as a guide, by combining foods that together include plus signs across the first three columns of Table 2.

Some of the more successful combinations of plant foods are legumes with whole grains (e.g., beans with rice; lentil soup with whole-grain bread); legumes with seeds (e.g., hummus made with chickpeas and sesame seeds); and whole grains with selected nuts/seedssesame, pumpkin and sunflower seeds; cashews and peanuts (e.g., whole-grain bread with tahini or peanut butter).

Because corn, unlike other grains, lacks tryptophan it is best combined with legumes and selected seeds or dairy (a taco with beans and cheese). Dairy can also be paired with whole grains and legumes to round out the amino acid profile required by the body (e.g., oatmeal with milk; yogurt with granola; black bean soup with sour cream; chili with cheese topping).

Bridging Some Gaps: Vitamin B12, Iron, and Antioxidants and Fiber

Of course, in concentrating on food combinations to build a good balance of amino acids, we should not lose sight of some of the bodys other nutritional requirements.

Vitamin B12. Key ideas to remember are that familiar plant foods are not good sources ofvitamin B12 and also that vitamin B12 becomes more difficult to extract from animal protein as people age. In addition, vitamin B12 is a critical vitamin both for brain and cardio-vascular health: Vitamin B12 deficiency is linked to brain dysfunction and memory loss. Vitamin B12 also partners with vitamin B6 and folate to contain homocysteine. Homocysteine is a by-product of metabolism that is linked to inflammation, blood clots and cardio-vascular disease. It follows that strict vegans who do not supplement with vitamin B12 can suffer from cardiovascular disease, just as people often do who consume large amounts of animal proteins. Some plant-based foods/supplements that do contain vitamin B-12 include brewers yeast; some sprouts; fermented soy products; and spirulina.

Iron. Heavy reliance on plant proteins may also result in iron deficiency because the non-heme iron of plant foods is of lesser quality and more difficult to absorb than heme iron found in meat. But, no matter whether you obtain iron through plant or animal foods, it is good to remember that iron is best absorbed when accompanied by vitamin C, as well as with traditional fats (since fats assist the absorption of minerals). Good plant sources of iron include whole grains; legumes; nuts and most seeds; leafy greens; dried fruits; and unsulfured molasses.

Antioxidants and Fiber. While fruits and vegetables cannot be counted on to supply protein requirements, they are, unlike animal proteins, rich sources of antioxidants and fiber. Antioxidants and fiber promote longevity and health and are essential components of a balanced diet. Plant foods are a rich source of three primary antioxidantsvitamins A, C, and Ealong with a broad array of other vitamins, minerals and phyto-nutrients. These work together to counter free radical damage, something that is the by-product of many kinds of environmental pollution as well as normal metabolic function.

A Note on Soy. While we might think from Table 2 that soy is the ultimate plant protein choice, keep in mind that most soy, about 80+ percent, is genetically modified. Also, soy is difficult to digest because it inhibits the digestive enzyme trypsin; it also inhibits the absorption of iron. The best soy products are those that are fermented and/or spouted, such as tempeh, tofu from sprouted soy, and miso. Many soy products, like soy milk, soy protein powders, concentrates, and isolates often contain denatured proteins without adequate cofactors needed for proper assimilation and metabolism. If you eat soy, try to use it sparingly as a component within a balanced diet.

Constructing Complete Proteins, Concluding Comment

Constructing complete proteins from economical plant sourcesto meet at least some of the daily protein requirement is not only cost-effective, but also efficient, because with a little planning, practice, and the right equipment, it can save time and effort in the end. Most recipes that use plant-based protein combinations, such as split peas and brown rice, can be cooked in large batches, frozen, and later defrosted for easy meals when you are in a hurry. Beans and grains can also be cooked in large batches and frozen in individual servings, to be defrosted and used to create an infinite variety of practically instant nutritious meals.

Remember that beans and grains are best soaked before cooking to remove phytates. This is easy to do, either by drawing water and allowing legumes and grains to soak overnight or by doing this in the morning before leaving the house for the day. Once you develop the habit, it seems easy. Planning ahead is the hardest part, something that becomes second nature with practice.

If you are not familiar with recipes that use legumes and grains, the following short Recipe Section may help get you started. I will follow up soon with more plant-based, complete-protein recipes to suit different tastes, budgets, and styles of cooking.

Reading Resources:

Lavon J. Dunne, Nutrition Almanac

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Livestocks Long Shadow

Sareen S. Gropper, Jack L. Smith, James L Groff, Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism

Elson Haas, Staying Healthy with Nutrition

IHE Delft, Virtual Water Trade

Frances Moore Lappe, Diet for a Small Planet

David and Marcia Pimentel, Sustainability of Meat-Based and Plant-Based Diets and the Environment

PBS.org, Is Your Meat Safe?

Jeanne Yacoubou, Factors Involved in Calculating Grain/Meat Conversion Ratios

Newsletters:

February 2010: Investing in Stocks [Bone Stocks]

May/June 2012: A Chicken with Gratitudethe Food ChainAnd the Hidden Dangers of Soy

April/May 2013: Alkalizing Foods to Prevent Disease

Recipes: Combining Animal- and Plant-Based Proteins

Success in the kitchen is often rooted in having the right time-saving equipment, knives, and pots and pans of good quality. A large stock pot, a no-fail rice/grain cooker that can be set in advance, and a slower cooker (even better, several of varying sizes) can save you time, effort, and allow you to cook in large batches and freeze for easy convenience.

The first two recipes below are delicious, economical family favorites. They combine animal- and plant-based proteins and work as good transitional recipes for people who expect animal proteins in every meal. With time, the proportions of meat to grains and the amount of vegetables can be adjusted to suit the family budget, tastes, and protein needs. The last recipe for Mjudra isvegetarian; it is economical, delicious, and just plain fun!

Bistro White Chili (Makes 15 cups, serving 15)

1 cup chopped onion

2 tablespoons minced garlic

cup olive oil

1 tablespoons ground cumin or to taste

1 pound ground turkey

2 pounds skinless boneless turkey breasts, cut into inch cubes

2/3 cup pearl barley

2 one-pound cans chickpeas, rinsed and drained

1 tablespoon minced bottled jalapeno pepper (wear rubber gloves) or to taste

6 cups chicken broth

1 teaspoon dried marjoram

teaspoon dried savory, crumbled

1 tablespoons arrowroot, dissolved in cup water

1 cup coarsely grated Monterey Jack cheese (about 1 pound)

cup thinly sliced scallion

- In a large pot, cook the onion and garlic in the oil over moderately low heat, stirring until the onion is softened; add the cumin, and cook the mixture, stirring for 5 minutes.

- Add the ground turkey and cubed turkey; cook the mixture over moderate heat, stirring until the turkey is no longer pink.

- Add the barley, chickpeas, jalapeno pepper, broth, marjoram, and savory and simmer the mixture, covered, stirring occasionally for 45 minutes.

- Stir the arrowroot mixture, add it to the chili, simmer, uncovered, stirring, for 15 minutes.

- Season the chili with salt and pepper, ladle it into heated bowls, and sprinkle it with the Monterey Jack and scallion.

Easy, Economical, and Hearty Vegetable Beef Barley Soup (12 one-cup servings)

pound lean ground beef

cup chopped onion

1 clove garlic, minced

7-8 cups low-sodium beef stock, or 7-8 cups water and 2 low-sodium beef bouillon cubes

One 14 oz. can unsalted whole tomatoes, un-drained, cut into pieces

cup pearled barley

cup sliced celery

cup sliced carrots

teaspoon basil, crushed

1 bay leaf

One 9-oz package frozen green peas; or frozen mixed vegetables

- In a 4-quart saucepan or Dutch oven, brown meat. Add onion and garlic; cook until onion is tender. Drain.

- Stir in remaining ingredients except frozen vegetables.

- Bring to a boil. Reduce heat and cover, simmering for 50-60 minutes, stirring occasionally.

- Add frozen vegetables and cook 5-10 minutes until tender (less if using peas).

Additional water can be added if soup becomes too thick upon standing.

Mjudra

2 cups lentils

1 cup brown rice

6 yellow onions, chopped

4 cloves fresh garlic, diced fine

3 teaspoons high quality sea salt

8 cups high quality water

2 Tablespoons coconut oil

- Rinse lentils and place in soup pot with 5 cups water and 1 teaspoons sea salt. Cover pan, bring to a boil. Turn down and let simmer until lentils are tender. About 45 minutes 1 hour. Drain lentils and return to soup pot.

- Rinse rice and place in separate saucepan with 3 cups water and 1 teaspoons sea salt. Cover pan, bring to a boil. Turn down heat and let simmer very low (without opening lid) for 45 minutes. Remove from heat and allow to rest for 5-10 minutes before opening. Open pan and fluff rice with a fork. Add rice to lentils.

- Saut onions in coconut oil and caramelize. Just before onions are finished cooking add fresh garlic and saut. Do not burn garlic. Add onion mixture to lentils. Stir everything together and serve with chopped onions on top or with fresh avocado and red pepper seeds.

Source: Todays Abundant Living

Copyright 2014 Pathways4Health.org